Let’s consider a weight matrix $W$. Typically, the weight matrices in a dense neural networks layers have full-rank. Full-rank means many different things mathematically. I think the easiest explanation of a $d$-dimensional matrix (let’s consider a square matrix $,M \in \mathbb{R}^{d,d}$) being full-rank is one in which the columns could be used to span (hit every point) in $d$-dimensional space. If you consider $d=3$, a matrix like

\begin{equation} M = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} \end{equation}

is not full-rank. $M$ has rank 2; notice that no combination of $(a,b,c)$ (that is no linear combination of the columns of the matrix) could solve the following equation

\begin{equation} \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} = a \times \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} + b \times \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} + c \times \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}. \end{equation}

$M$ has rank $2$ because it has two linearly in-dependant rows, because it has a column span of 2, because its’ null space is 1, and a whole list of other mathematical explanations. What is important, is that for large dimensional space, sometimes you might have a rank which is far lower than $d$.

Imagine a one thousand dimensional matrix ($d=1000$).

In our square matrix case, we will have a matrix with 1000 rows and 1000 columns. Storing such a large matrix is in-efficient if the rank was something like $200$. This is precisely why LoRa is so useful. Large language models are thought to have a low intrinsic dimension. The authors of the LoRa approach propose that we could apply lower dimensional weight updates when training. We achieve this by manipulating the weight update matrix’s size.

When we’re updating the weight matrix, at each step we’re figuring out how to slightly alter the values in our matrix. To visualize in a low dimensional case, we’re doing something like

$$ \begin{aligned} W + \Delta W &= \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} -0.00002 & -0.001 & 0.000 \\ 0.00003 & 0.0002 & 0.00001 \\ 0.01 & -0.0001 & 0.003 \end{pmatrix} \\ &= \begin{pmatrix} 0.99998 & -0.001 & 1.000 \\ 1.00003 & 0.0002 & 1.00001 \\ 1.01 & 0.9999 & 0.003 \end{pmatrix} \end{aligned} $$

But if $d$ is large, the matrix $\Delta W$ will contain lots of values. We’re doing lots of calculations, and this is costly. And importantly, if $W$ has a low intrinsic dimension, we can assume that we may not even need to perform this update to each and every row of $W$. Remember, a matrix having a rank $r < d$ implies that the information stored in the matrix could be stored in something with $r$ dimensions instead of $d$.

The authors propose that you could describe $\Delta W$ as the product of two smaller matrices. Remember, in this case $\Delta W$ has dimension $(d \times d)$. The rules of matrix multiplication tell us that if we take matrix $A$ with dimension $(d \times r)$ and $B$ with dimension $(r \times d)$ then $A \times B$ has dimension $(d \times d)$. So what they suggest, is simply letting $\Delta W = A \times B$ for $A,B$ described above for some chosen $r$. The golden thing to remember is that for multiply matrices:

\begin{equation} W (d \times d) = A (d \times r) \times B(r \times d) \leftrightarrow W (d \times d) = \Delta W(d \times d) \end{equation}

But why, you might wonder? What does this matrix decomposition give us? Well, importantly, now instead of having $d^2$ values in $\Delta W$, as we would if it had dimension $(d \times d)$, we have $2 \times (r \times d)$. Before LoRa, we had $d^2$ entries to compute and now with LoRa we have $2\times r\times d$. So now let’s consider an example.

Example. Consider a weight matrix with dimension $10,000$. Before applying LoRa, we’d have $10,000 \times 10,000 = 100,000,000$ values in our update weight matrix. Now, let’s apply LoRa with $r = 100$. We’re saying instead of using $\Delta W$ with dimension ($10,000 \times 10,000$), let’s use $\Delta W = A \times B$ where $A$ has dimension $(10,000 \times 100)$ and $B$ has dimension $(100 \times 10,000)$. Instead of 100 million values, we now have just $2 \times 100 \times 10,000 = 2,000,000$. We’ve reduced the number of values we’re updating by a factor of 50.

When LoRa is implemented, we typically also scale our update to the weights $\Delta W$. We use the update $\frac{\alpha}{r} \Delta W$.Increasing $\alpha$ will increase the size (and thus affect) of our weight update relative to the initial weights. We take $\alpha$ to be constant in $r$. This means that if we took $r=50$ or $r=20$, we implement $\alpha$ such that the size of the weight matrix update would be the same.

ReLora

Using regular LoRa, we describe our weight update matrix as $\Delta W = A \times B$ where $A$ has dimension $(d \times r)$ and $B$ has dimension $(r \times d)$. The resulting matrix, $\Delta W$, can have at most rank $r$. We remember the fundamental rule from maths that

\begin{align} \text{rank}(A + B) &\leq \text{rank} (A) + \text{rank}(B) \end{align}

Because using LoRa the update we make is restricted to rank $r \leq d$, what this really means is that the weight update we apply isn’t of full rank. However, maybe we want to try to apply an update to the weight matrices with as high a rank as possible. To do this, the authors essentially propose applying LoRa multiple times. Say we choose to perform three LoRa updates. Enumerate these $\Delta W_1, \Delta W_2$ and $\Delta W_3$. Then we have that

\begin{equation} \Delta W = \Delta W_1 + \Delta W_2 + \Delta W_3 \end{equation}

Our total weight update is described as the sum of the three component updates. Each of these three updates has, at most, rank $r$. Thus, the important conclusion we can draw is that

\begin{equation} r \leq \text{rank}(\Delta W_1) + \text{rank}(\Delta W_2) + \text{rank}(\Delta W_3) = \text{rank}(\Delta W) \end{equation}

Therefore, the dimension of the rank update we would have achieved with LoRa $(r)$ is less than or equal to the dimension of the rank update using ReLoRa. However, a number of practical considerations must be made. First of all, how do we implement these three weight updates with respect to the original optimization process?

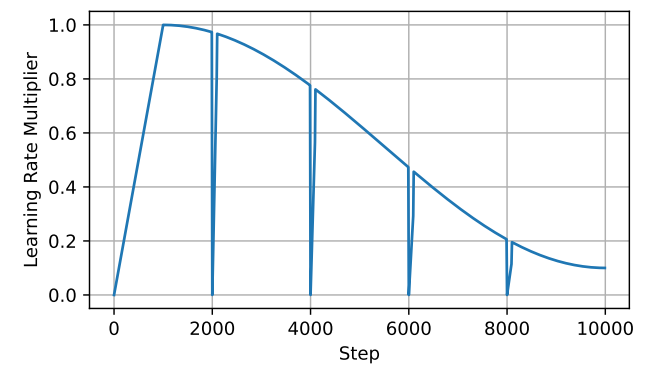

The first thing we need to do is implement a scheduler. This scheduler controls the learning rate. We want to ensure that upon starting to produce a new set of weight updates, i.e. $\Delta W_4$ for instance, we reset the learning rate to $0$. We also ensure that we have set $99%$ of the low-magnitude optimizer state values to zero too. All this means is that the vast majority of our optimizer state values that are close to zero, we will simply set to zero for each new $\Delta W_i$ we look to produce.

The type of scheduler we use here is called a Jagged Cosine Scheduler. In the above image, you can see that $4$ different updates have been made. At each update, the learning rate is set to zero. There is a brief warm up period for the learning rate after the reset, the authors suggest 50-100 steps.